Con el buen ojo que nos tiene acostumbrados Geraldinho, en su post recuerda al Negro Dolina en la presentación del libro de AF y cita el siguiente párrafo que muchos encontrarán muy parecido a su última alocución en TVR Dice Dolina:

"Hay un pensador barcelonés, Jorge Wagensberg, que sostiene que la lectura, el fenómeno literario, es un acto binario, que se produce entre dos conciencias parecidas. Él dice que el escritor tiene que parecerse un cacho al lector, que tiene que haber como un aire de familia. Porque si el libro es demasiado complejo para el que lee, sobreviene un falta de interés parecida al aburrimiento. Y si por el contrario, el libro es demasiado simple para el que lee, pues sobreviene el desdén. Entonces hay casi como un casamiento entre el autor y el lector.

Sin embargo, uno podría objetar esta idea por elitista, porque viene a decir que es necesaria una competencia para leer un libro. Yo creo que efectivamente es así. Pero lo peligroso es deslizar esta idea que uno tiene acerca de los libros, a saber, que hay que tener cierta competencia para poder entender lo que el libro dice, a, por ejemplo, la voluntad popular. Y creer que es lo mismo votar que leer un libro de física. Creen, algunos, que la voluntad popular consiste en acertar, con un concepto científico previo. Hay una verdad previa, y el votante va al cuarto oscuro y acierta o falla. Y no se dan cuenta de que no es que haya un concepto previo que hay que acertar, sino que el acto mismo de la voluntad... ES LA VERDAD. No es que estamos acertando o fallando un blanco previamente marcado, sino que al votar establecemos el lugar en donde el blanco está".

Mi comentario a Geraldinho fue mas o menos el siguiente:

En la programación de video juegos, para que sea entretenido el mismo debe transcurrir dentro de una franja óptima entre dificultad y destreza. Me explico: si hacemos un gráfico en donde abscisas y coordenadas son la dificultad en jugarlo y la destreza en aprenderlo, habría una línea a 45º que sería un juego piola que se lo puede ir manejando pero a medida que se avanza se hace mas dificultoso y entretenido.

Los estudiosos de esto se dieron cuenta que no es una línea ese estado de fluidez del juego donde el juego transcurre de forma agradable, sino una banda paralela a la recta mencionada en donde el jugador (lector en este caso) va tomando destreza (hasta que se aburre) entonces intenta con una mayor dificultad ( hasta que se frustra) entonces retoma la senda de la destreza hasta estar listo para el próximo escalón. A esto lo llaman Flow o estado de flujo, descripto en Flow The Psychology of Optimal Experience de Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi que se puede bajar desde aquí, también se lo conoce como extasis o ecstasy.

Creo que tanto en la lectura (banda de éxtasis voluntaria y ampliada a nuestro gusto), como en el dificilísimo video game de elegir a quién votar (franja muy angosta y rigurosa), el tipo de juego es lo mismo, salvo que en la votación el juego pierde continuidad, o como en el ajedrez se piensa mucho y la acción es poca.

Tratando de refutar el ultimo párrafo de Dolina, en la escalerita del éxtasis algunos estamos principiando el juego, otros mas viejos y mas sabios estamos unos escalones mas arriba. De lo que se trata no es en dónde en la escalera del Flow uno se encuentre, en que nivel del juego accedamos a la votación, lo importante es sentir placer, ese éxtasis que produce el votar, ni pánico ni subestimación, involucrarse para poder sentir que de alguna manera uno la mueve. (como ejemplo que esto no se trata de una cuestión elitista puedo citar a mi hija Lara que va a votar por primera vez este año, su juego recién empieza, ella lo verá de una forma totalmente distinta a mi, que socio-culturalmente podemos decir que estamos en el mismo escalón)

Para terminar cito textualmente a Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi

In our studies, we found that every flow activity, whether it involved competition, chance, or any other dimension of experience, had this in common: It provided a sense of discovery, a creative feeling of transporting the person into a new reality. It pushed the person to higher levels of performance, and led to previously undreamed-of states of consciousness. In short, it transformed the self by making it more complex. In this growth of the self lies the key to flow activities.

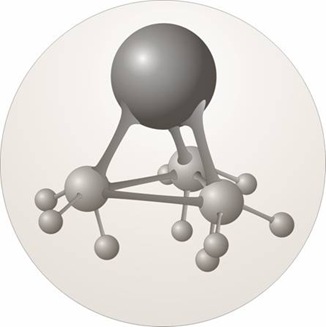

A simple diagram might help explain why this should be the case. Let us assume that the figure below represents a specific activity—for example, the game of tennis. The two theoretically most important dimensions of the experience, challenges and skills, are represented on the two axes of the diagram. The letter A represents Alex, a boy who is learning to play tennis. The diagram shows Alex at four different points in time. When he first starts playing (A1), Alex has practically no skills, and the only challenge he faces is hitting the ball over the net. This is not a very difficult feat, but Alex is likely to enjoy it because the difficulty is just right for his rudimentary skills. So at this point he will probably be in flow. But he cannot stay there long. After a while, if he keeps practicing, his skills are bound to improve, and then he will grow bored just batting the ball over the net (A2). Or it might happen that he meets a more practiced opponent, in which case he will realize that there are much harder challenges for him than just lobbing the ball—at that point, he will feel some anxiety (A3) concerning his poor performance.

Neither boredom nor anxiety are positive experiences, so Alex will be motivated to return to the flow state. How is he to do it? Glancing again at the diagram, we see that if he is bored (A2) and wishes to be in flow again, Alex has essentially only one choice: to increase the challenges he is facing. (He also has a second choice, which is to give up tennis altogether— in which case A would simply disappear from the diagram.) By setting himself a new and more difficult goal that matches his skills—for instance, to beat an opponent just a little more advanced than he is—Alex would be back in flow (A4). If Alex is anxious (A3), the way back to flow requires that he increase his skills. Theoretically he could also reduce the challenges he is facing, and thus return to flow where he started (in A1), but in practice it is difficult to ignore challenges once one is aware that they exist.

The diagram shows that both A1 and A4 represent situations in which Alex is in flow. Although both are equally enjoyable, the two states are quite different in that A4 is a more complex experience than A1. It is more complex because it involves greater challenges, and demands greater skills from the player.

But A4, although complex and enjoyable, does not represent a stable situation, either. As Alex keeps playing, either he will become bored by the stale opportunities he finds at that level, or he will become anxious and frustrated by his relatively low ability. So the motivation to enjoy himself again will push him to get back into the flow channel, but now at a level of complexity even higher than A4.

It is this dynamic feature that explains why flow activities lead to growth and discovery. One cannot enjoy doing the same thing at the same level for long. We grow either bored or frustrated; and then the desire to enjoy ourselves again pushes us to stretch our skills, or to discover new opportunities for using them.

Agradezco al antropólogo ex bloguero Esteban S por haberme introducido a esto, esperamos su regreso

0 nos acompañaron:

Publicar un comentario